March 2016 3

Art and Health

The idea that the arts, or creativity in general, are good for the body and soul is nothing new. In fact, there are a lot of studies around it, especially regarding the effects of art therapy on groups combating disease (i.e. Alzheimer’s) or psychological trauma.

What about art for the artist’s soul and health? Undoubtedly, this same idea applies.

Once, I went to visit a very dear friend and mentor in the hospital only months before he passed away. I’ll never forget seeing him with a sketchbook and a full set of colored pencils sprawled out across a tray next to his bed. When I joked that he never stopped working, he said, “Of course not. It’s like breathing for me.”

Talking with another friend recently, we agreed that even after a long dry spell, an artist inevitably gets an itch to make something if for no other reason than to “get it out.” It feels good.

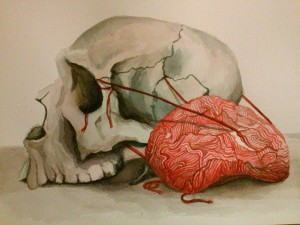

When I make something, it’s often inspired by a feeling, an emotion or sensation. It may derive from joy, sadness, loneliness, silliness, or in today’s case pure anger- and I needed to get it out.

“Knee” doesn’t look angry; it wasn’t meant to. But its creation certainly exercised my own anger. And I think something delicate, maybe even beautiful, came out of it.

Whatever it is you like to do, be it sing, write, draw, paint, sculpt, design or perform, go do it. It’s good for your health.

The Hunter and the Hunted: Antoine-Louis Barye, Master Animalier

It’s beneficial to study other artists’ work. And nothing can discount the importance of seeing art in person. Photographs and computer screens just can’t compare. So, in honor of the many creators out there, I’m dedicating a series of posts to artists, active and not, whose work grabs my attention when I wander out to galleries and museums. This post, about Antoine-Louis Barye (1796-1875), will be the first:

“Horse Surprised by a Lion,” Bronze, ca.1857

It wasn’t my first visit to the Baltimore Museum of Art. It wasn’t the first time I wandered through its collection of European Art. It wasn’t even my first encounter with this particular artist’s work, although at the time when I laid eyes on the sculpture pictured above, I hadn’t realized it.

I was drawn to the fluid movement erupting from the lion’s exacting clutch and coursing like electricity through that horse’s veins, through its flared nostrils and finally escaping as a terrified shriek from its agape mouth. What energy, what careful attention to anatomy and detail.

The exhibit text explained that Barye was like a scientist, often studying animals in the Paris zoo and observing dissections. His predatory sculptures depict not only nature’s unrelenting food chain, but many saw them as symbolism for government figures in the brutal struggle for power. In fact, he received several government commissions for monuments in France.

“Panther Seizing a Stag,” Bronze, ca. 1850

Seriously, guys, pictures don’t do them justice. You need to see casts of his sculptures in person to fully appreciate just how precisely Barye articulated every detail of his subjects’ musculature down to the direction their fur grows.

Get out and see some art!

“Lion with Serpent,” Bronze, ca. 1832

“Roger and Angelica Borne by the Hippogriff,” Bronze, ca. 1840

Seeing into the past

As social media likes to dredge up the memories we committed to the internet, it reminded me today of a very nice and not so distant one. Two years ago, I finished and gave my dad a portrait of his birth mother, Edith. Neither of us had the chance to meet her – she passed two days after he was born. Regardless, I know she was a large influence for him.

Looking at this photo today made a few gears start turning and compelled me to write.

In a recent post, I described the act of creating as the practice of seeing, observing and translating. I left out one detail I think many creative types can agree they experience often: you never stop observing more, and as a result you see the things you could have done differently in your previous work.

It’s not to say that I’m unhappy with the portrait of my grandmother, but there are things I see now that I didn’t before. Taking a step back and looking at it with fresh eyes, I realize I flattened out the planes of space on the left side of her face, and perhaps outlined her teeth less subtly than I should have among a few other things. I won’t go back and do a thing to the drawing because I know it brings my dad joy as it is.

Maybe the aforementioned detail can be said of all things in life. When you leave them behind and revisit them days, weeks, months, or years later, your perspective is inherently different because of all that you have seen and observed in the meantime. Wisdom.

My dad loves to take photographs. He’s done it ever since he was much younger than I am now. Photographs of things we may take for granted…leaves blanketing a forest floor, the snow falling around a lit lamp post, the patterns in tree bark, the winding fence posts that trail off into the horizon, the way light and shadows fall upon a person’s face. My dad loves to see and observe. That’s part of why he’s so wise – and I’m not just saying that because I’m biased (well, maybe I am, but I write in earnest when I say he’s one of the wisest human beings I know and I happen to keep the company of many very smart people). Just as my dad’s “mum” was influential for him, so too is he for me. He taught me how to see and observe.

It’s so easy to stop at seeing. We move from one stimulant to another in milliseconds. But, if you take a minute to observe what you’re seeing, you may comprehend what you couldn’t before – in your art and in your life.